A LONGITUDINAL STUDY ON CHILDHOOD AND ADOLESCENCE ONSET PSYCHOSESINTERVENTIONAL STRATEGIES AND MODALITIES OF EVOLUTION

The childhood psychoses represent a major public health problem. Through this, appears the necessity of early detection aiming the implementation of some early intervention strategies and further follow-up.

Objectives: the prospective identification of children with a high probability to develop a psychotic disorder, the recognition of the vulnerability markers in the “high risk” groups, the early detection and prevention of a first psychotic episode, the approach of optimal intervention strategies, the minimalizing of the duration of untreated psychosis-DUP and further long period follow-up of the diagnostic stability in time.

Methods: In our study, accomplished during the period 2000-2011 on the two groups – 90 children with psychotic onset and the control group – 77 „high risk” children having psychotic parents, we applied the following standardized instruments: K-SADS-PL, CBCL- Child Behavior Checklist, SCL 90 – Symptoms Checklist, FAD- Family Assessment Device, PANSS-Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale. From the 77 „high risk” children group, 40 received therapy and support in a complex strategic intervention program.

Results: Through one way ANOVA, we obtained statistically significant correlations, p<0,001, between CBCL-SCL/SCL-FAD scores. CBCL showed high internalization=28 /externalization=32 scores, in both groups. Through the CBCL-SCL correlation: high obsessive values in parents determine high internalization scores in children. SCL-FAD correlation: a strong positive relation between the parent’s symptoms and the disturbed family functioning. The total mean PANSS score was 89.03 ± 20.1, the positive symptoms score 23.8±6.5 and negative score 20.02±8.8.There were significant positive correlations between negative symptoms, long DUP and a poor outcome. (Spearman’s p =0.012).

Conclusions: Through therapy, only 10% of the “high risk” children developed psychosis in comparison to 35% in the group of children who didn’t receive therapy, proving the fact that the onset can be delayed or even prevented. DUP remained a significant predictor of outcome, proving to be a proper target for secondary prevention.

INTRODUCTION

The fact that treatment delay – the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) in children and adolescents – is associated with a range of poorer outcomes for patients with psychosis, is well-known. Treatment delay is also recognized as one of the few predictive indicators amenable to change, being therefore a high priority for clinical and research programmes engaged in the field of child and adolescent mental health.

The psychotic symptoms appear usually 1-2 years before the diagnosis of psychosis is put through clear-cut DSM IV criteria and KSADS-PL confirmation.

Previous research showed that the risk of developing a mental disease, respectively psychosis gets higher when multiple adverse conditions are accumulated (Rutter, 1994; Kolvin 1988).

We already know that DUP comprises several facets, including delay in help seeking, delay in referral to services and delay within mental health services. Each of these situations may require different intervention strategies to achieve the optimal effect.

It is understood that alongside this work, public health initiatives are vital to reduce delay by engaging the public with programmes increasing awareness and reducing stigma.

Service systems research indicates that effective health promotion programmes should include multi-level strategies comprising the children’s families, neighbourhoods, schools and communities [5]. We will present a description of some of the novel approaches currently in progress, encouraging prompt access to appropriate treatment and early intervention.

OBJECTIVES

Through the study, we aimed: the prospective identification of children with a high probability to develop a psychotic disorder, the recognition of the vulnerability markers in the “high risk” groups [1,2], the early detection and prevention of a first psychotic episode, the approach of optimal intervention strategies, in order to reduce the duration of untreated illness -DUI, respectively of the untreated psychosis – DUP [9].

Through our applied research interventions we aimed at both understanding and influencing the reasons for delay in accessing appropriate treatment.

One of our objectives has been to increase awareness and to reduce stigma concerning psychotic disorders in children and adolescents.

MATERIAL & METHODS

Our study consists of a retrospective research (2000-2007) as well as a prospective research performed between 2007-2011 in the Clinic of Psychiatry and Neurology for Children and Adolescents Timisoara. The Ist step of the study was composed of the identification of children and adolescents, which needed ambulatory care or were inpatients of our clinic and developed a first psychotic episode. The present study is part of a larger pilot study on a number of 90 patients-children and adolescents with a diagnostic of first psychotic episode.

We assessed for each patient, besides the clinical parameters: the prodrome’s duration, the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and the duration of untreated illness (DUI).

We included in our control group 77 help seeking “high risk” children, offspring of parents with schizophrenia or affective psychoses, who were in the evidence of our clinic for different psychopathologic disorders.

Inclusion criteria:

A diagnostic of psychotic disorder, according to DSM IV, K-SADS-PL

Age < 19 years

The global PANSS score had to be in the value interval 60-120

Monoparental or biparental families, children being raised in the family

The informed consent to participate in the study, given by the parents as well as the child

For the selection of the „high risk” children cases we took as inclusion criteria the accessibility of children and families in order to apply our instruments and also the presence of one parent suffering from psychosis (nonaffective, affective) [3].

Our study group as well as the control group was examined for associations with variables contributing to delay in help seeking, delay in referral and delay in getting appropriate treatment. The compulsory evaluations included: the phase evaluation of the clinical, neurobiological markers and reevaluations applying the standardized instruments.The instruments were applied in parallel on the two groups: 90 patients with psychoses and 77 „high risk” children from families with one psychotic parent.

We approached the following instruments: CBCL-Children Behavior Checklist, SCL 90-Symptoms Checklist, FAD-Family Assessment Device, PANSS-Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale.

KSADS-PL was applied in order to confirm the diagnoses.

Additionally we applied the SIPS-Structured Interview for Prodromal Symptoms in the „high risk” children group, in order to identify some markers of conversion to psychosis in this vulnerable population.

CBCL includes 118 items referring to behavioral and social competence problems of children, evaluated by parents.

The SCL 90 is very often used as screening for psychopathology(Kaplan, 2000).The 90 items are grouped in 9 scales. Concerning the validity of the test, the inner consistence for clinical situations, reported by the authors was between r = .79 and r = .89, the intercorelation of the scales being r = .45; the reliability test-retest after 1 week = .73 and .92.

Through FAD we evaluated the family functioning, being especially important for families with a member with mental disorder. Previous research showed that the risk of developing a mental disease gets higher when multiple adverse conditions are accumulated (Rutter, 1994; Kolvin, 1988).

PANSS was applied, in order to offer an objective measure for the psychiatric symptoms. The description given for each symptom and the 7 ankor points set, specific for each symptom offered an coherent scoring method. We applied the PANSS scale in order to evaluate the intensity and evolution of symptoms through time in different time points.

Through PANSS we evaluated the positive, negative and general symptoms in our study group [4].

We used: descriptive statistics-average, standard deviation, absolute and relative frequencies, parametric statistical tests-simple ANOVA and simple factorial ANOVA; the Pearson correlation test to check for the presence of statistically significant correlations between the CBCL-SCL 90 results, the CBCL-FAD and the SCL 90-FAD results; as well as the Pearson correlation test to check for the presence of statistically significant correlations between the course of illness and other various clinical parameters (DUP, the prodrome duration). We had the support of the SPSS statistical program as well as MedCalc.

RESULTS

The results were analyzed through parametric statistical tests: simple ANOVA and simple factorial ANOVA, with the support of the SPSS statistical program.The independent variables were: the age, sex, clinical diagnosis, the family type (disordered parent). The dependent variables were the scores obtained through the application of the instruments.

1. The CBCL Scores Analysis

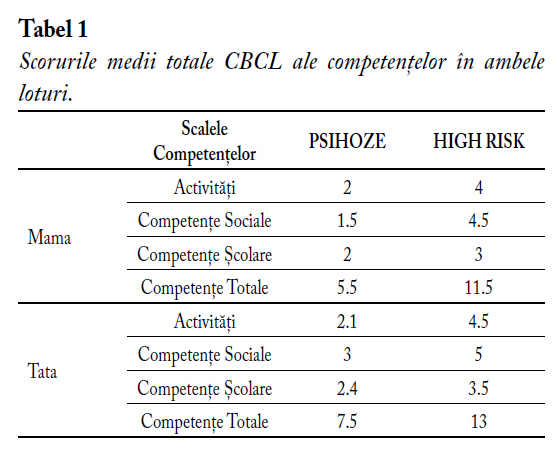

Concerning the CBCL total social competencies scores, the 90 patients with psychoses group registered lower median total competencies scores, especially lower social competencies scores than the “high risk” children group.

The “high risk” children group proves to have lower median social competencies total scores than the population in non-clinical range. These values in “high risk” children prove the fact that a high percentage of children with psychotic parents show a dysfunctional social functioning (Table 1).

Table 1. CBCL median competencies total scores for both groups.

The scores for behavioral problems in both studied groups showed high values for aggressiveness and depression.For the group of children with a first psychotic episode (Bender 2006): all patients show high scores for aggressiveness, depression, the scores being much higher than those in the “high risk” group. In this group the externalization, as well the internalization scores are much higher than in the “high risk” group. In the high risk children group, all the children having a parent suffering from psychosis, showed high scores for depression, hyperactivity and aggressiveness.The boys showed high externalization scores (hyperactivity, aggressiveness). The girls showed high internalization scores (depression, avoidance, somatization).

Figura 1 – The Median Global CBCL Scores in both groups.

For the comparison of the results obtained through CBCL for both children groups we applied One Way ANOVA test, this showing that there were statistically significant differences (p<0,001), between the scores obtained for each group. So that, the children from the group with a first episode psychosis showed higher global CBCL scores (fig.1).

2. The SCL-90 Scores Analysis

We obtained the highest scores for the variables obsessive-compulssiveness, depression, sensitivity and paranoid ideation for mothers as well as for fathers. The scores obtained by the mothers are higher, resulting the fact that the mothers are more affected by their children’s psychopathology. As well, the scores obtained by the families with a psychotic parent are much higher than those obtained by the parents having a child with a first episode psychosis (fig.2).

Figura 2 – SCL-90 Median Total Scores in both groups.

3. FAD Results Analysis

We obtained high FAD scores for the ”high risk” children group, especially for the mothers, respectively for the psychotic parent, for the variables roles, affective responsiveness, and for the fathers for the behavioral control. Both groups are strongly affected, concerning the global family functioning.

The Correlations Analysis

Through one way ANOVA correlations between CBCL-SCL / SCL-FAD scores, we found statistically significant values, p<0,001.The CBCL showed high internalization=28 / externalization=32 scores – depression, hyperactivity, aggressiveness and anxiety in both groups. The SCL showed high anxiety, depression and obsessive-compulsive scores for the parents in both groups. The FAD showed high scores for communication, affective responsiveness, role distribution and control problems. SCL-CBCL correlations: high obsessive values in parents determine high internalization scores in children and high depression and anxiety values determine high total CBCL scores and through SCL-FAD correlations: strong positive relation between the parent’s symptoms (sensitivity, depression) and disturbed family functioning (affective responsiveness, implication).

The total mean PANSS score was 89.03 ± 20.1, the positive symptoms score 23.8±6.5 and negative score 20.02±8.8. We found, higher negative symptoms PANSS scores in the “high risk” group, the negative symptoms appearing as a genetic marker, ~2 years before the active psychosis phase [4]. There were significant positive correlations between negative symptoms, long DUP and a poor outcome. Poor insight was correlated with symptom severity and poor global functioning (Spearman’s p =0.012).

We found statistically significant correlations between adequate therapy, early intervention strategies and the diagnostic evolution in the “high risk” children group, at follow-up after 5 years (Figure 3.).

Figura 3 – High risk group diagnostic evolution.

DISCUSSIONS

Through our study, we observed that particularly, the awareness of insidious features such as functional decline and social withdrawal as signs of prodromal psychosis in children and adolescents, is a significant pathway for early detection and intervention .

In conformity with the actual international research results, we noticed that subclinical psychotic experiences during adolescence represent the behavioural expression of liability for psychotic disorder.

Although, some results of the present study are similar with results of other studies, it gives a greater importance and attention to the parameters of first psychotic episode in children and adolescents, but also for the response and evolution after specific interventions [6, 7,12].

The revealed aspects through this study offer further implications and perspectives for future research in the field of mental health promotion, implementation of strategies and early intervention programmes in child and adolescent psychoses, as well as for the necessity of future development of our services. One of our future aims would be to develop a common care pathway for early intervention teams in the region with agreed standards.

CONCLUSIONS

Ensuring adequate opportunities for the diagnostic and early intervention in cases of first psychotic episodes in children and adolescents can play a determinant role in the short and long term course of first psychotic episode [12]. Early intervention in the prodromal or even premorbid phase, is very important for children and adolescents, because developing psychosis in this age has signifigant impact and outcomes, interrupting the normal course of development.

The vulnerable child has some characteristics, which put him in a risk position.If proper intervention strategies are applied, the vulnerability can be balanced through protective factors [11].So that we have to work on the rehabilitation of the child as well as on the family disfunctionalities.

Through therapy, only 10% of the “high risk” children developed psychosis in comparison to 35% in the group of children who didn’t receive therapy, proving the fact that the onset can be delayed or even prevented. DUP remained a significant predictor of outcome, proving to be a target for secondary prevention [8, 10]. Through proper intervention strategies the QOL-quality of life of the patients and their families can be ameliorated, as well as the prognostic of patients with psychosis. We achieved new perspectives, through new diagnostic and monitorizing methods, through the implementation of a complex model of interventions and strategies.

We found that all the diagnostic concepts were provisory through the evolution perspective, so that proper intervention strategies are significant for these age groups.On long term, we noticed a high diagnostic interindividual variability. In our studied groups, the prognostic was very poor especially when the psychosis onset was very early (9-12 years). We noticed a more severe prognostic for the cases with very early onset of psychosis or with a longer DUP and in the cases with predominantly negative symptoms [6,7].

A better prognostic was achieved for the cases with an acute onset, with predominantly positive symptoms and with a good premorbid functioning.

Abreviations

TOC – Tulburare obsesiv-compulsiva

MDI – întârzieri și dizabilitați developmentale multiple

ADHD -Tulburare hiperkinetica cu deficit de atenție

OCD – Obsessive-Compulsive disorder

MDI – Multiple Developmental Impairments

ADHD – Attention deficit hyperkinetic disorder

Bibliography

- Alaghband-Rad J, Hamburger SD, Giedd JN, et al: Childhood – onset schizophrenia: biological markers in relation to clinical characteristics. Am.J Psychiatry 154:64-68, 2000.

- Asarnow RF, Nuechterlein KH, Fogelson D, et al : Schizophrenia and schizophrenia –spectrum personality disorders in the first degree relatives of children with schizophrenia : the UCLA family study.Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:581- 588, 2002.

- Bell RQ (1998) Multiple – risk cohorts and segmenting risk as solutions to the problem of false positives in risk for the major psychoses. Psychiatry 55:370-381.

- Bettes, B.A.& Walker, E. Positive and Negative Symptoms in Psychotic and other Psychiatrically Disturbed Children . Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 2000, 28, 555-68

- Connor C., Birchwood M., Patterson P. DUP-A Focus on Current European Strategies-The Birmingham CLAHRC/YOUTHspace Programme – targeting DUP in a UK urban environment. Early Interv Psych, 2010, 4:11-14

- Henry LP, McGorry PD, et.al. Early psychosis prevention and intervention.Centre long-term follow-up study of FEP: methodology and baseline characteristics. Early Interv Psych, 2007;1:49-60

- Johannessen JO, Friis S, Joa I, et. al. First episode psychosis patients recruited into treatment via early detection teams versus ordinary pathways: course, outcome and service use during first 2 years. Early Interv Psych, 2007;1:40-8

- McGorry PD, Henry LP. Evaluating the importance of reducing the DUP. Psychiatry 2000;34:145-9

- McGorry PD, Phillips LJ (2004) The close-in or ultra high risk model. A safe and effective strategy for research and clinical intervention in prepsychotic mental disorder, Schizophrenia Bulletin 29:771-790.

- Norman RMG, Lewis SW, Marshall M. Duration of untreated psychosis and its relationship to clinical outcome. Br J Psych 2005; 187(48):19-23

- Philips LJ, Yung R, McGorry PD: identification of young people at risk of psychosis : validation of Personal Assesment and crisis Evaluation Clinic Intake criteria. Australian N.Z.J. Psychiatry; 2005;34 suppl.:S 164-16.9

- Singh SP. Early Intervention in psychosis: a reappraisal. Br J Psych, 2010; 196:343-5